Review | 8 February 2026

Volume 13 Issue 1 pp. 57-75 • doi: 10.15627/jd.2026.4

Daylight Enhancement Strategies for Historic Buildings: A Critical Review of Interventions, Their Constraints, and Applicability

Nurefşan SÖNMEZ,1,2,* Arzu CILASUN KUNDURACI3

Author affiliations

1 Department of Architecture, Graduate School, Yaşar University, Izmir, Bornova, 35100, Turkey

2 Antwerp Cultural Heritage Sciences (ARCHES), Faculty of Design Sciences, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Mutsaardstraat 31, 2000, Belgium

3 Department of Architecture, Faculty of Architecture, Yaşar University, Izmir, Bornova, 35100, Turkey

*Corresponding author.

nrfsnsonmez@gmail.com (N. SÖNMEZ)

arzu.cilasun@yasar.edu.tr (A. CILASUN KUNDURACI)

History: Received 24 September 2025 | Revised 27 November 2025 | Accepted 13 December 2025 | Published online 8 February 2026

2383-8701/© 2026 The Author(s). Published by solarlits.com. This is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Citation: Nurefşan SÖNMEZ, Arzu CILASUN KUNDURACI, Daylight Enhancement Strategies for Historic Buildings: A Critical Review of Interventions, Their Constraints, and Applicability, Journal of Daylighting, 13:1 (2026) 57-75. doi: 10.15627/jd.2026.4

Figures and tables

Abstract

With the growing urgency to reduce carbon emissions in the built environment, enhancing daylight availability in historic buildings has become a critical and challenging task due to the required balance between environmental sustainability objectives and cultural heritage conservation principles. This paper presents a systematic and critical review of 54 studies focusing on daylight enhancement strategies in historic buildings, published between 2000 and 2025. Following the PRISMA scoping review method, this review investigates intervention challenges according to three primary constraints: regulatory and conservation limitations, material and structural constraints, and climate-responsive requirements. By mapping currently employed daylighting techniques in historic buildings and critically assessing their underlying assumptions, this study aims to bridge the gap between performance-driven daylighting research and cultural heritage preservation principles. The findings are intended to promote multidisciplinary discourse and serve as a basis for creating contextually acceptable, ethically responsible, and technically feasible daylighting recommendations for historic buildings.

Keywords

daylighting strategies, visual comfort, historic buildings, architectural heritage

1. Introduction

The built environment accounts for about 40% of carbon emissions related to energy across the world [1]. Given the increasing impacts of climate change, this highlights the critical necessity of emphasizing sustainability in the architectural context. Research demonstrates that conserving existing buildings leads to much lower environmental impacts compared to construction of energy-efficient new buildings, thereby supporting both environmental and cultural sustainability [2]. This is largely because most of the buildings’ carbon emissions are related to the energy used for heating, cooling, and lighting [3]. Therefore, integrating sustainable principles into the conservation of historic buildings not only honors their legacy but also allows them to adapt to contemporary needs while maintaining their inherent value [4].

Among various strategies, daylight optimization is not only an energy-saving measure, but also a key to maintaining the spatial integrity and authenticity of interiors. Daylight, which includes sunlight, skylight, and their reflections from surrounding surfaces, is a crucial element in creating healthy indoor environments and has an important role in forming the built environment [5]. Considering that people spend most of their time indoors for activities such as work, education, living, socializing, and circulation [6-8] ensuring efficient and well-balanced daylighting provision becomes crucial. When carefully designed, daylight can improve physical, mental and visual comfort; increases productivity; and reduces dependence on artificial lighting, thereby reducing energy consumption [9-11].

Achieving environmental sustainability in historic buildings requires addressing several important factors including optimizing daylight availability, providing uniform daylight distribution, minimizing energy consumption, and preventing excessive solar gain [12]. To solve daylight-related problems, design strategies like optimizing the WWR, altering glazing types, installing daylight-directing elements or using exterior shading elements are often necessary. These methods often work well for contemporary buildings, but historic buildings need to be handled with caution due to their cultural and heritage value. Maintaining the authenticity of these buildings requires stricter restrictions on interventions like adaptive reuse and renovation, with each intervention needing careful consideration to preserve the buildings’ historical integrity [10,13].

Although the studies on daylighting strategies are increasing, most of them focus on general design principles or evaluation interventions in contemporary buildings. Historic buildings, however, present unique challenges due to regulatory restrictions, their built techniques, and climate-dependent constraints. While some research has addressed daylighting in historical contexts, there is still a lack of systematic and critical reviews that examine how such interventions align with conservation principles and architectural values. Any intervention must be reasonable in terms of the building’s original design, materials and structural systems (architectural integrity) [14], minimizing permanent impact as much as possible, enabling the building to be returned to its prior condition (reversibility) [15], and applying contemporary interventions in an integrated and harmonious way (compatibility with heritage values) [16]. Without addressing these issues, improvements in environmental performance could compromise the cultural and architectural integrity of historic buildings. Given the importance of this topic, this study aims to critically review daylight enhancement strategies for historic buildings, focusing on their architectural integrity, reversibility, and compatibility with heritage values. The objective of this scoping review is to consolidate and critically map existing research in order to guide future design interventions that necessitate both improved environmental performance and the conservation of architectural and cultural heritage.

2. Methodology

The review is organized around three core challenges: (1) regulatory and conservation limitations, (2) structural and material constraints, and (3) climate-responsive needs. Within this framework, key daylighting strategies - glazing, shading, and roof-based systems are examined within the discussion of each specific challenge, assessing their daylighting performance potential. This review follows a scoping review design, using PRISMA only as a reporting framework [17]. This method, which has been widely used in several studies focusing on light in architecture [18-20] was chosen, because the aim was to identify, map, and discuss the concepts and characteristics in the relevant literature, rather than to answer a specific research question as in a systematic literature review [21].

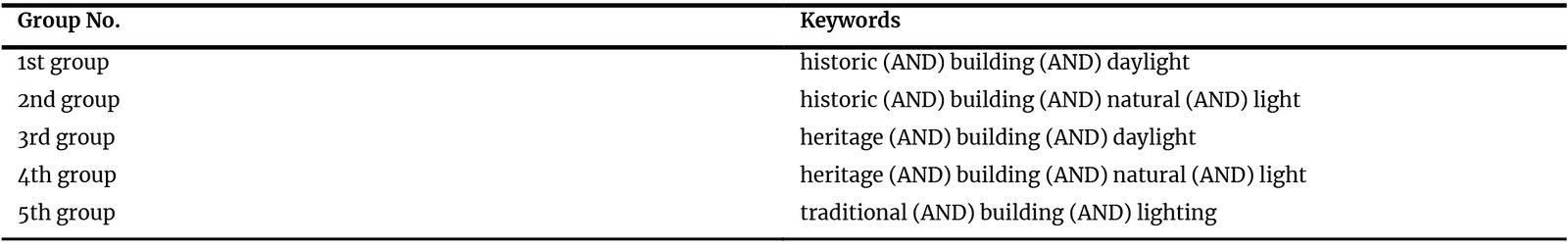

The first author performed the review by using English keyword searches as given in Table 1. The interdisciplinary focus of this study on daylight enhancement in historic buildings necessitated access to a wide range of literature, including case studies from real-world retrofits, architectural science, and conservation theory. Google Scholar was purposefully chosen as the main search tool because, although traditional databases like Scopus and Web of Science are skilled at indexing peer-reviewed journal articles, it also retrieves important but frequently overlooked gray literature that is crucial to our research. This includes conference proceedings, theses, and book chapters addressing vernacular architecture and local regulations.

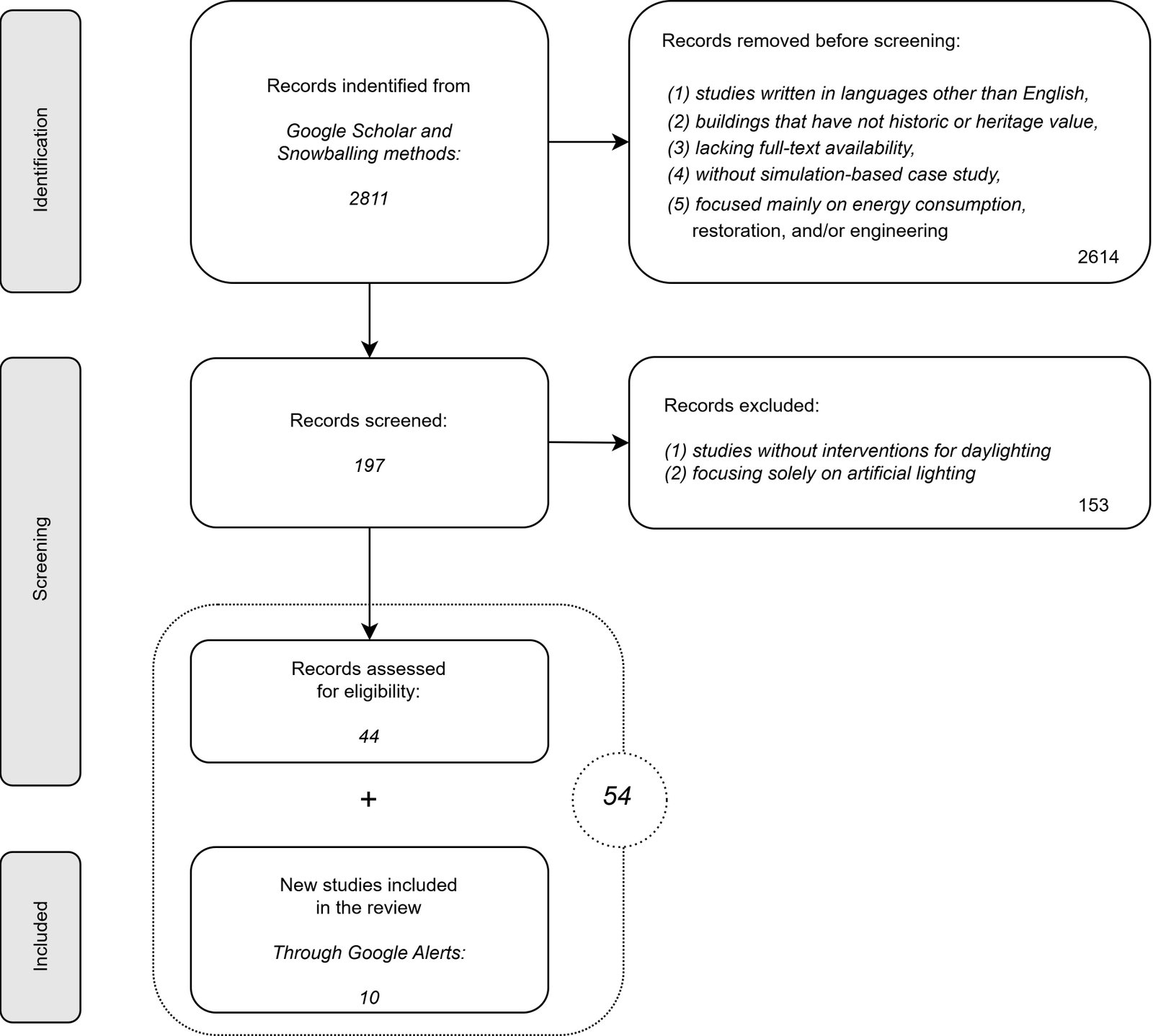

The literature review process was conducted over an extended period, from January 2023 to July 2025. For each keyword group, the first 40 pages were scanned on Google Scholar. Fig. 1 shows the selection process of the reviewed studies and an illustration based on the Prisma flow diagram. First, the studies were excluded if they (1) were written in languages other than English, (2) did not address buildings with historic value, (3) lacked full-text availability, (4) did not include simulation-based case studies, and (5) focused mainly on energy consumption, restoration, engineering, or only artificial lighting. A total of 197 studies were initially reviewed. Second, 153 of them were excluded as they did not focus on daylighting interventions and/or they focused solely on artificial lighting. The original dataset consisted of the remaining 44 studies. Throughout the review period, new publications identified via Google Scholar Alerts were continuously screened, and those meeting the specified criteria (10 studies) were incorporated into the dataset. In total, 54 studies were reviewed thematically. Out of 54 studies, majority of them (37) were published as journal articles (68 ), while 12 were presented as conference or symposium publications (22 ). The remaining studies include 2 book chapters, a master’s thesis, a doctoral dissertation, and a research report.

Figure 1

Fig. 1. PRISMA-based flow diagram illustrating the selection process for the literature review.

3. Review results

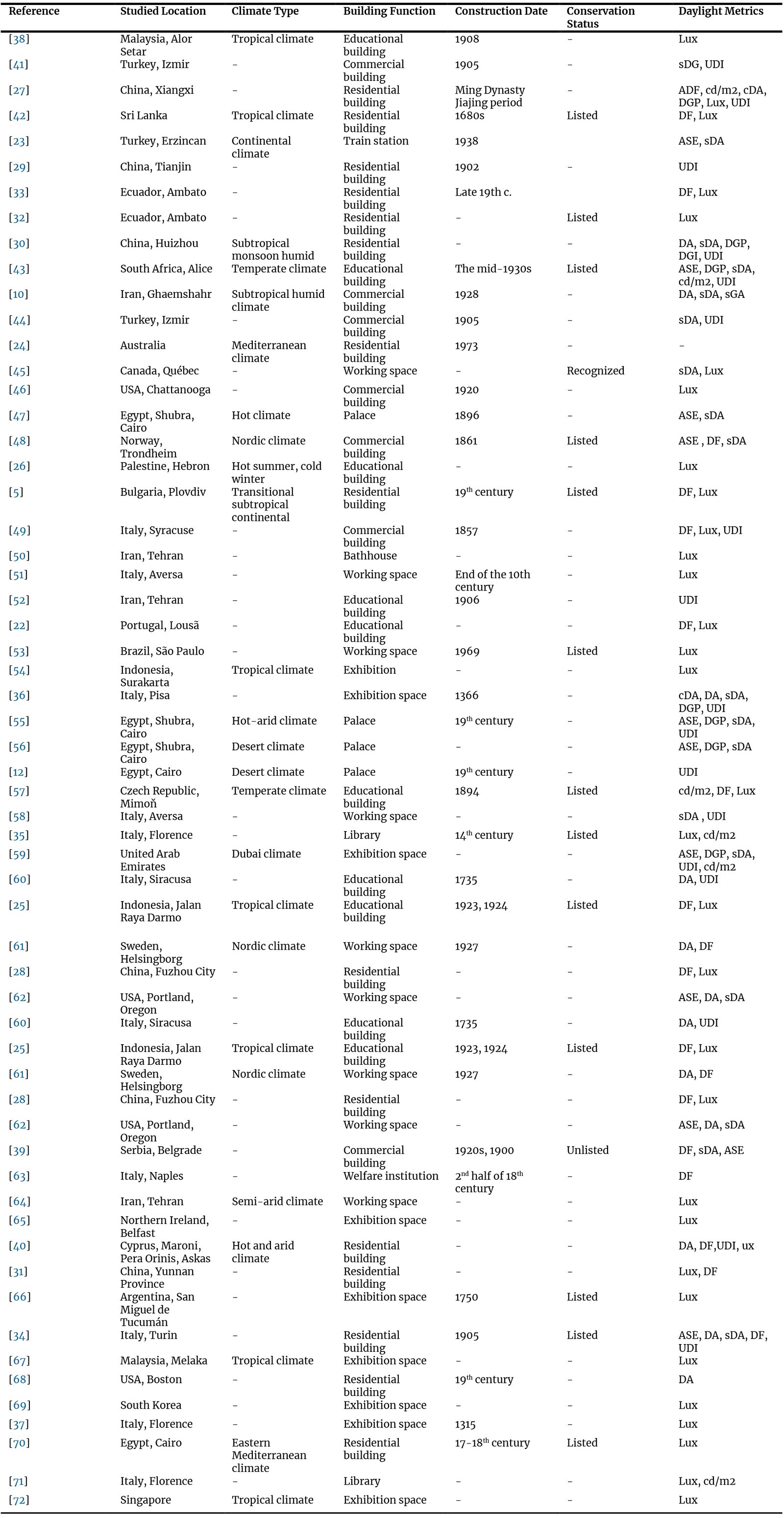

A structured data extraction table was developed summarizing each study’s climate context, building function, conservation status, construction period, and the daylight metrics employed Table 2. This allowed for consistent cross-case comparison and helped identify patterns and gaps within the reviewed literature.

The largest proportion of studies was conducted in Italy, accounting for 20.83% of the total. This was followed by China and Egypt, each contributing 10.42%. Research carried out in Iran represented 8.33% of all studies, while those originating from Turkey and the United States each comprised 6.25%. In contrast, a considerable number of countries were represented by only a single study; together, these 18 countries made up 37.50% of all studies included in the review. The review shows that the tropical climate is the most common climate mentioned in the studies, making up 25% of all identified climate references. It is followed by temperate, Nordic, and desert climates, each representing 8.33% of the total. Many other climate types -such as subtropical monsoon humid, subtropical humid, Mediterranean, hot climate, hot-arid climate, semi-arid climate, continental, transitional subtropical continental, Eastern Mediterranean, and Dubai climate appear only once. In addition, in 30 out of 54 studies, climate type was not mentioned, meaning that more than half of the studies lacked information about climate conditions. When the geographical and climatological classifications of these unspecified locations are considered, 19 of them fall into warm or temperate climate zones, while 7 are in cold or cool climate regions. This distribution shows that most studies focus on buildings in Mediterranean, subtropical, and tropical climate zones, while fewer studies examine examples from cold or continental climates.

The building functions show a clear focus on residential and cultural uses. Out of 54, 14 buildings (26 ) are residential, 9 buildings (17 ) are exhibitional, 8 buildings (15 ) are educational, 7 buildings (13 ) are commercial, and 7 buildings (13 ) are working spaces. The remaining 9 buildings (17 ) include 4 palaces, 2 libraries, a bathroom, a welfare institution, and a train station. This distribution suggests that the reviewed research mainly concentrates on daylight performance in residential, cultural, and educational buildings. Notably, 37 of the studies did not provide any information on the construction period of the examined buildings. Among those that did, 13 buildings were identified as dating to the early 20th century, while 2 were built in the late 20th century. In addition, 9 buildings were found to originate from the 19th century, and 10 others were built prior to the 19th century. Only 15 out of 54 reviewed studies (28%) explicitly identified the conservation status of buildings (e.g., listed, unlisted, or registered), even though this factor directly affects the feasibility of interventions. Moreover, only 4 studies [22-25] consider conservation constraints by referring to policy documents and daylight performance in an integrated manner, even though this relationship is essential for determining which interventions can be realistically applied in protected buildings.

Methodologically, most studies (56%) rely on only static daylight metrics such as Illuminance and Daylight Factor (DF), which fail to capture the seasonal changes of daylight. Table 2 highlights a misalignment between climatic contexts and the daylight metrics used. For instance, studies in tropical and hot climates continue to rely on static metrics such as DF and Lux [5,25,26], even though dynamic metrics would better capture seasonal variability. About 44% of studies adopt dynamic metrics such as such as ASE (Annual Sunlight Exposure), sDA (Spatial Daylight Autonomy), and UDI (Useful Daylight Illuminance) [12,23,27], which provide yearly evaluation of daylight performance. Furthermore, studies often mention national daylight standards from Bulgaria [5], China [27-29] Ecuador [32,33], Indonesia [25], Italy [34-37] Malaysia [38], UK [39-40] as well as international standards and guidelines developed by organizations such as ANSI/IES, CEN, CIBSE, CIE, and IESNA (10 studies), and rating/certification systems including BREEAM and LEED (8 studies). However, few studies assess whether the proposed interventions comply with these daylight standards or certification criteria, which may reduce the applicability of their recommendations in professional practice.

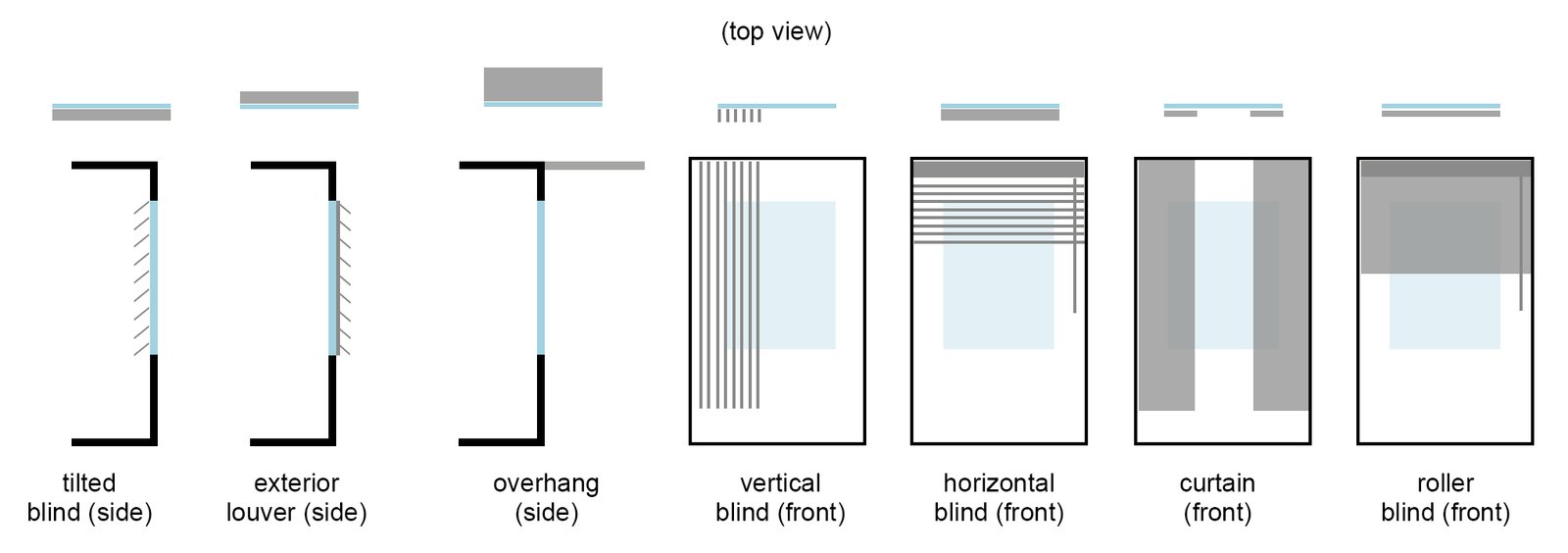

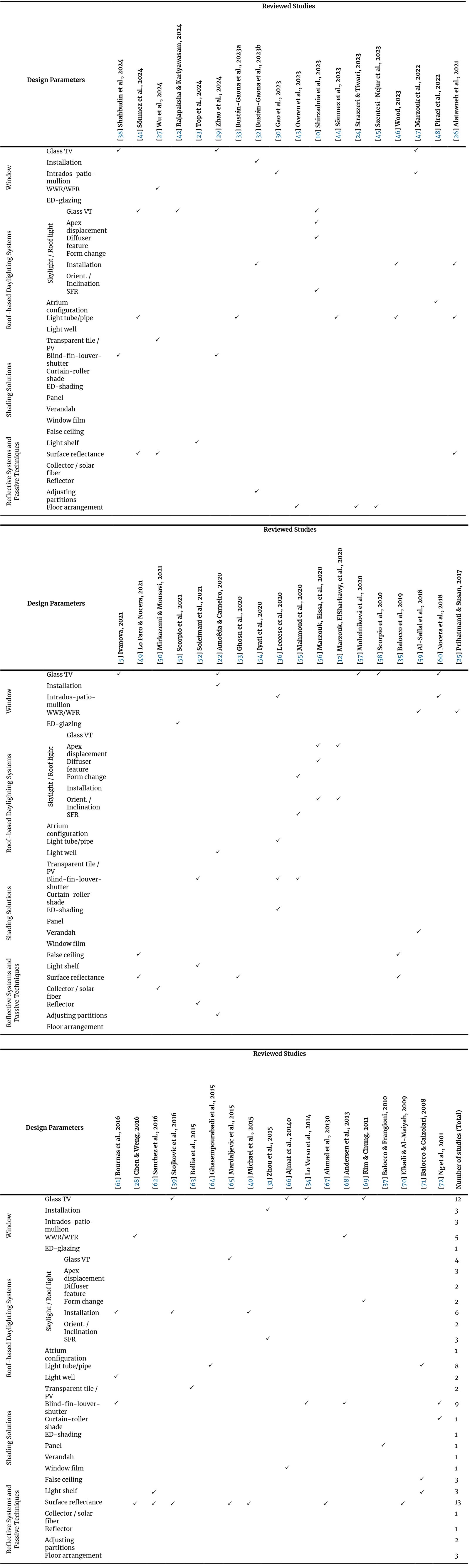

Following the analysis of publication types and sources, the review proceeded to examine the content of these studies in terms of their design parameters and intervention strategies. The subsequent results highlight the most commonly investigated design parameters and strategies, as detailed in Table 3. Roof-based daylighting systems (35) are the most studied category. Within this group, skylight/rooflight modifications (16) are examined more frequently than new installations (6) and both are more commonly investigated than window installation (3). Among light-directing strategies -such as light tubes/pipes, light wells, and transparent tiles/PV- light pipes/tubes are the most frequently studied (8), particularly after 2021. Strategies to improve daylight availability, including window systems (21) and roof-based systems (35), are studied more often than strategies to control excessive daylight, such as shading solutions (15). Within shading solutions, partial and adjustable elements such as blinds, fins, louvers, and shutters (9) are the most examined. Architectural elements that are unique to historic buildings, such as intrados and mullions, have been examined in only 3 studies. For surface reflective strategies designed to enhance uniform daylight distribution -such as false ceilings, light shelves, and altering surface reflectance (19) emerge as the most studied approach, particularly before 2016. Partition adjustments (2) have appeared only within the past five years, whereas floor arrangement strategies (3) are observed exclusively in 2023 studies.

Recommendations from the reviewed studies regarding daylighting enhancement strategies frequently include adjusting glass VT by increasing the number of glass pane [5,34,47,57,60] adding window and skylight openings [32], increasing the size of existing window and skylight openings [10,27,28,59] optimizing existing skylight feature [10,12,55-56,69] increasing surface reflectance [28,62,68] integrating light-reflective elements such as false ceiling [49,52,60] and light shelves [23,71], incorporating light-directing strategies such as light tubes/pipes [26,46,54] and light wells [22,61], and optimizing spatial configuration [43,45]. Recommendations regarding daylighting control or reduction strategies often involve using shading elements, especially louvers [38,52,72], reducing surface reflectance [35,65,67], using low-transmittance curtains [72], reducing window opening size [36], applying electrical-driven (ED) shading [51], and ED glazing [58].

Reviewed studies propose a wide range of daylighting interventions, yet their effectiveness varies depending on climate, building typology, and methodological approach. Research on opening configurations shows that changing WWR or WFR can substantially improve daylight performance in residential and educational buildings. For example, Gao et al. [30] demonstrated that widening patios and increasing window-edge height in a residential building in China increased UDI from 9.5% to 56.6%, however, glare risk rose as DGP increased from 4% to 26.5% in a subtropical monsoon humid. Similarly, Chen and Weng [28] showed that a 1/7 increase in WFR significantly improved daylight distribution, achieving lighting coefficients of up to 20.4% in a humid subtropical climate, representing a substantial improvement over base case condition.

In contrast, museum studies emphasize daylight control rather than enhancement; Al-Sallal et al. [59] found that reducing WWR to 5% and increasing verandah depth improved UDI from 83% to 97%, while reducing ASE to 0%, demonstrating how typological constraints influence design decisions. Glazing-related strategies also reveal notable conflicting outcomes. Comparative studies indicate that while double glazing with moderate VT values often provides a balanced outcome between daylight availability and visual comfort, triple glazing or low-transmittance ED glazing can reduce glare but may compromise sDA or daylight levels. Nocera et al. [60] reported that replacing clear glass (0.75 VT) with double glazing (0.60 VT) resulted in more balanced daylight and reduced glare probability in a Mediterranean climate, while Mohelníková et al. [57] showed that double glazing with VT 0.81 increased classroom illuminance compared to triple glazing with VT 0.73 in a temperate climate. Scorpio et al. [58] demonstrated that ED glazing increased sDA to 97.2%, but when switching to a lower-transmittance ED mode for glare control, sDA dropped to 66.6%, representing a 31% reduction in useful daylight in a Mediterranean climate.

Shading systems also highlight the influence of climate and façade orientation on daylight performance. Soleimani et al. [52] showed that inward-tilted blinds maintained target illuminance (300–3000 lux) for 57.1% of occupancy hours, outperforming horizontal blinds (41.9%) and outward tilted blinds (25.4%) in Iran’s semi-arid climate. The same study also found that interior vertical fins further improved performance by up to 7.6% compared to all three blind configurations. In tropical climates, Shahbudin et al. [38] demonstrated that external louvers effectively reduced peak illuminance in a tropical climate, emphasizing the role of climate-responsive shading. Andersen et al. [68], meanwhile, found that active shading on north-facing façades could outperform passive shading, although this advantage lowered or disappeared on south-facing façades in Boston’s continental climate, highlighting the importance of orientation-specific design. Roof integrated daylight systems also offer varied results across climates and building types. Skylight modifications -such as adjusting inclination angle, apex position, or diffuser materials- have been shown to reduce ASE by over 20% while improving UDI. For example, Mahmoud et al. [55] reported that reducing the SFR from 100% to 30% cut ASE by more than 20% and decreased cooling loads significantly in a hot climate. Light tubes demonstrate even larger impacts: Iyati et al. [54] found that introducing light tubes in a tropical climate increased the percentage of area achieving 300 lux from 6-14% to 92.76%, while Sönmez et al. [41] showed UDI improvements of up to 300 % and glare reduction of 67.74 % in a Mediterranean climate. Comparative work in Palestine by Alatawneh et al. [26] revealed that light tubes in a hot climate increased indoor illuminance by at least %70, whereas skylights improved it only by %9.

Just as shading elements and roof-integrated daylighting systems exhibit climate- and geometry-dependent performance, façade-based strategies such as light shelves also demonstrate similar context-specific behaviors. The geometry and material properties of light shelves play a significant role in shaping daylighting performance, and studies report varying results [62,71,73]. Kemer and Çelebi Yazıcıoğlu [73] showed that, in a Turkish educational building, wider light shelves (60 cm) markedly improved daylight metrics compared with narrower configurations (40-50 cm). Yet, the overall effectiveness of light shelves is highly dependent on spatial characteristics.

For instance, Sanchez et al. [62] found that in a deep-plan space, light shelves produced only a marginal reduction in sDA (17.5% to 17%) but substantially lowered ASE (10.2% to 5.9%) due to their shading effect. Similarly, Top et al. [23] demonstrated that, in a continental climate train station, light shelves decreased ASE while simultaneously increasing sDA. These findings emphasize that the performance of light shelves varies with building height, depth, and façade configuration; in some cases, they may even act primarily as shading devices. Consequently, optimizing light shelf parameters according to the specific context is essential to achieve an appropriate balance between solar control and daylight availability. Interior surface strategies, when considered alongside other daylighting interventions, provide additional improvements in overall daylight performance and distribution. Alatawneh et al. [26] and Andersen et al. [68] demonstrated that increasing surface reflectance enhances both daylight availability and its uniform distribution within interior spaces. Conversely, reducing reflectance in exhibition environments significantly lowered daylight exposure, as shown by Mardaljevic et al. [65], helping protect sensitive artifacts from excessive light levels. Overall, the literature demonstrates that effective daylighting solutions cannot be generalized; instead, their suitability depends on the interaction between climate, typology, and conservation constraints. The percentage changes reported across these studies clearly show how specific design decisions can either significantly enhance daylight availability or strategically control overexposure depending on the building context.

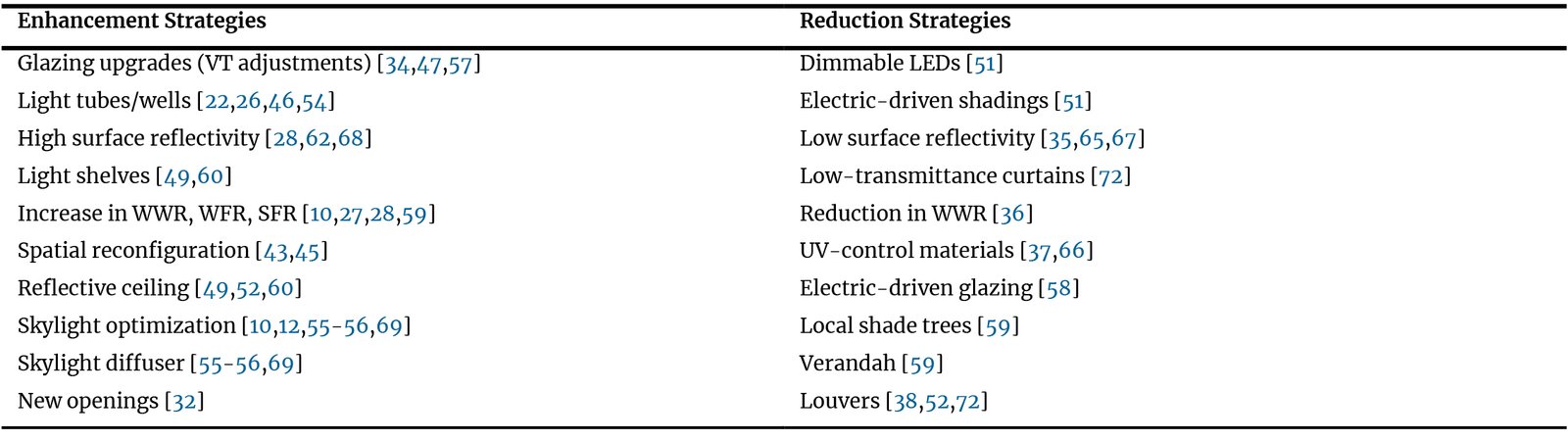

As shown in Table 4, the studies predominantly focus on similar types of enhancement aim to increase daylight availability through surface modifications, glazing adjustments, spatial reconfiguration, or roof-based interventions, whereas reduction strategies focus on solar control and the mitigation of glare and heat gain. Importantly, the feasibility and performance of these strategies vary significantly depending on regulatory restrictions, material characteristics, and climatic conditions, which are examined in detail in the following sections.

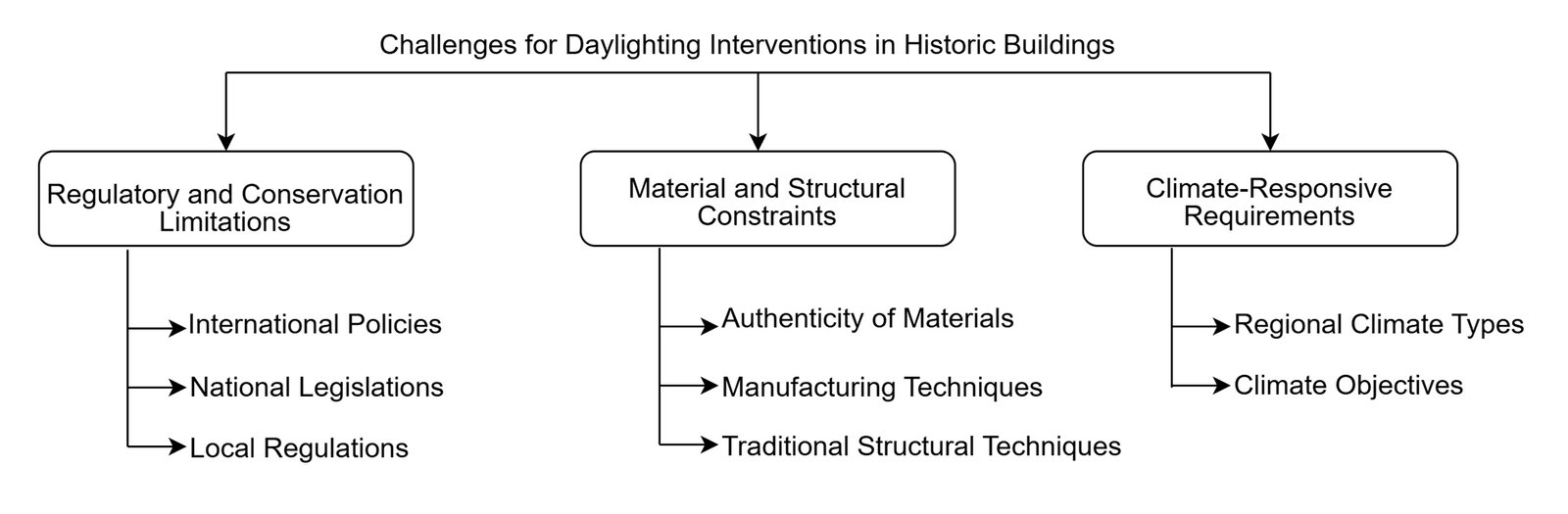

These above-mentioned strategies are generally easier to implement in non-historic buildings, where they do not face significant constraints. In the case of historic buildings, however, their applicability may be subject to various limitations, as given in Fig. 2. These challenges can be thematically grouped into three main categories: (1) regulatory and conservation limitations, (2) structural and material constraints, and (3) climate-based requirements, investigated respectively.

3.1. Regulatory and conservation limitations

Historic buildings present authentic materials and valuable craftsmanship under the protection of international charters (e.g., Venice 1964, Burra 1979, NARA 1994, Madrid 2012) and national legislation that favor minimal and reversible interventions while preserving authenticity [13,74-76]. These principles, while important for heritage conservation, directly limit daylighting upgrades: even small-scale actions such as replacing historic glass or adding shading elements often necessitate legal approvals and risk material and authenticity loss, altered façades, or reduced architectural integrity [13,77].

Consequently, designers face a constant conflict between conservation requirements and environmental performance goals, with strict heritage restrictions often forcing the reduction or abandonment of effective daylighting strategies, resulting in only modest improvements in building performance [39,53]. This tension between conservation and environmental performance is interpreted differently across national contexts. In some countries, such as Italy, where a historic building is under full conservation protection, legislative frameworks exclude historical and architectural heritage from energy retrofitting, since the primary focus is on conserving the building in its original state rather than enhancing livability [51]. Conversely concerns with energy efficiency and carbon reduction have led to the replacement of glass in historic buildings with energy-efficient alternatives [78].

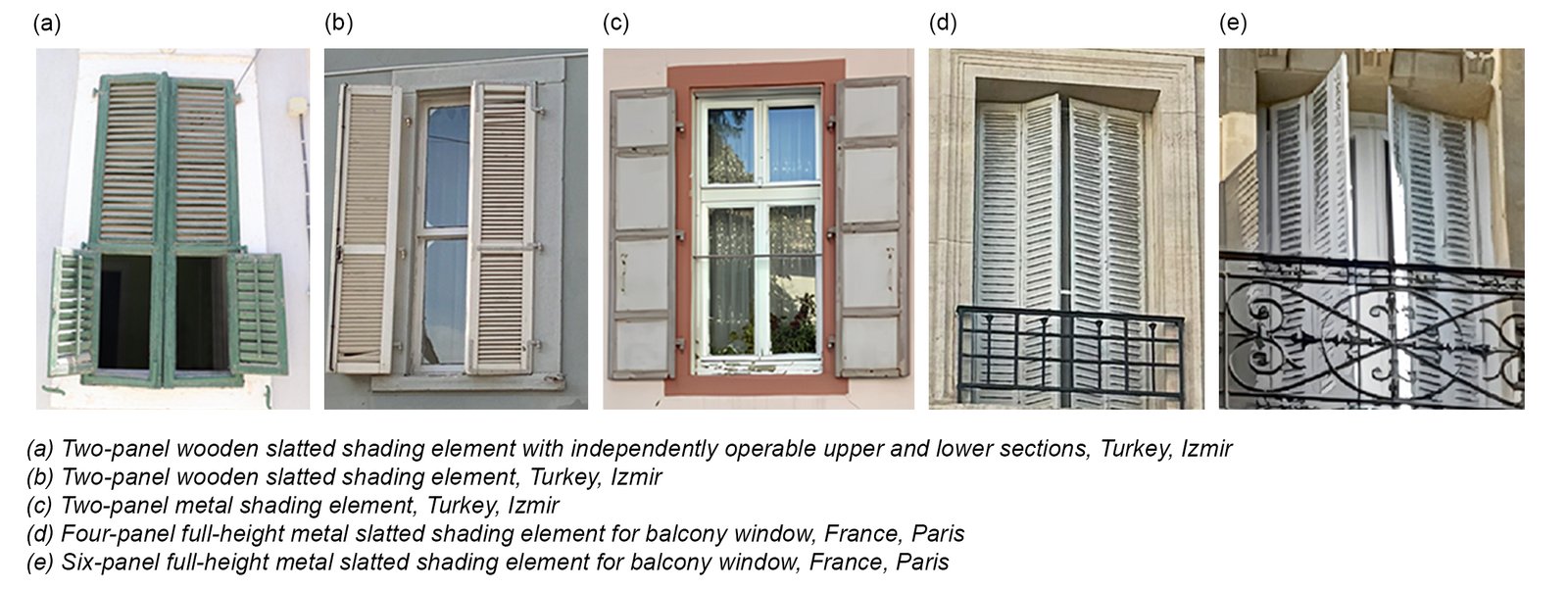

Conservation regulations also restrict façade interventions such as adding new openings, resizing windows, or altering window-to-wall ratios, as these can compromise architectural heritage and authenticity. Although such measures may be acceptable in cases of major reconstruction, they often conflict with reversibility and authenticity principles in historic contexts. Similarly, the selection of shading configurations internal or external, fixed or operable- must align with reversibility and authenticity requirements [13,76].

Fixed or externally mounted systems may entail permanent façade changes and significant visual impact [10], making reversible solutions more suitable for heritage buildings. Other strategies mostly passive in nature- include increasing interior surface reflectance by painting surfaces brighter or using reflective materials to enhance daylight distribution [26] or decreasing it by using darker tones or matte finishes to control daylight levels [35]. These strategies are typically reversible and compatible with heritage conservation principles, provided that the surfaces do not contain historically significant paintings, decorations, or tiles [79]. In cases where interior walls have heritage value but are not listed, temporary and movable wall panels or removable wallpaper can offer viable alternatives. By contrast, external painting that alters the original façade appearance often conflicts with conservation principles and may be deemed inappropriate [68].

Beyond surface-level reflectance adjustments, strategic spatial reconfiguration such as removing partitions, reshaping layouts, or replacing interior walls can dramatically boost daylight availability by allowing light to penetrate far deeper into the interior [45]. However, these transformations are typically irreversible, may compromise structural integrity, and often conflict with heritage conservation principles [68], making them unsuitable for protected buildings but highly effective in cases of major reconstruction or large-scale renovation.

3.2. Material and structural constraints

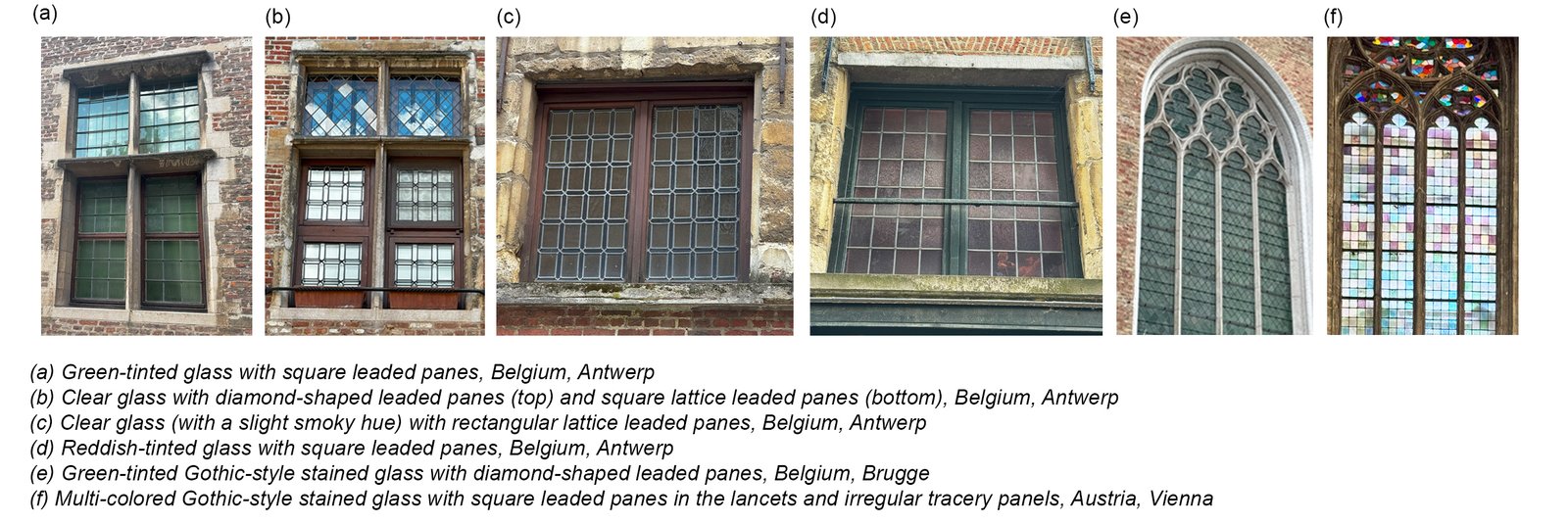

Historic buildings present traditional materials such as stone, earth, wood, brick, iron, and historic window glass [78], [80], whose physical properties and durability differ significantly from contemporary materials like concrete and steel. These materials are often vulnerable to deterioration and, due to their authenticity, are difficult or impossible to replace without loss of heritage value. Incompatibilities between existing (old) and contemporary materials, including differences in moisture behavior, thermal expansion, and surface texture, can cause cracking, surface degradation, and visual disruption, leading to strict conservation rules that may prohibit even minimal alterations such as painting or modifying exposed historic elements [53]. While materials like wood enrich interior authenticity, their low reflectivity can limit daylight distribution [31]. Similarly, historic window glass, typically small-paned, colored, and of lower optical quality (as demonstrated in Fig. 3) due to past manufacturing techniques and compositions, transmits less light than contemporary glazing [39,78,81]. These constraints emphasize both the challenges of preserving material authenticity and the untapped potential for sensitive daylight improvements through advanced glass technologies [82].

Upgrading windows with double or triple glazing, which has higher efficiency in terms of visual and thermal comfort, and energy performance are often proposed for historic buildings [5,34,47,57,60]. However, increased glass thickness and weight may require adapting or changing the original frame design and material, which can conflict with conservation principles [22]. When window frame intervention is restricted, secondary glazing may be a viable option, provided there is sufficient window depth, and the addition is not visible from the outside [83-84]. The substantial thickness of historic walls often enables the integration of a secondary window. Moreover, traditional wooden-framed windows allow for the replacement of existing glass sheets with thicker ones by inserting additional slim wooden frames [39,60]. If the window frame is not sufficient thick, slim-profile double glazing which relies on a reduced cavity filled with inert gas [85] - or vacuum glazing - which achieves even thinner profiles by creating a vacuum between panes [86] may be preferred. An alternative approach is the use of reversible window films, which help control excessive daylight and reduce solar heat gain [66,87]. In addition to passive glazing systems, electrical-driven glazing (ED) [58], which has ability to automatically adjust the transmittance levels and solar heat gain coefficients using sun-tracking sensors or material properties [88] is investigated to improve daylight availability in historic buildings. Beyond changing glazing type, this strategy also may bring structural problems in historic buildings due to the ED glazing’s heavier components.

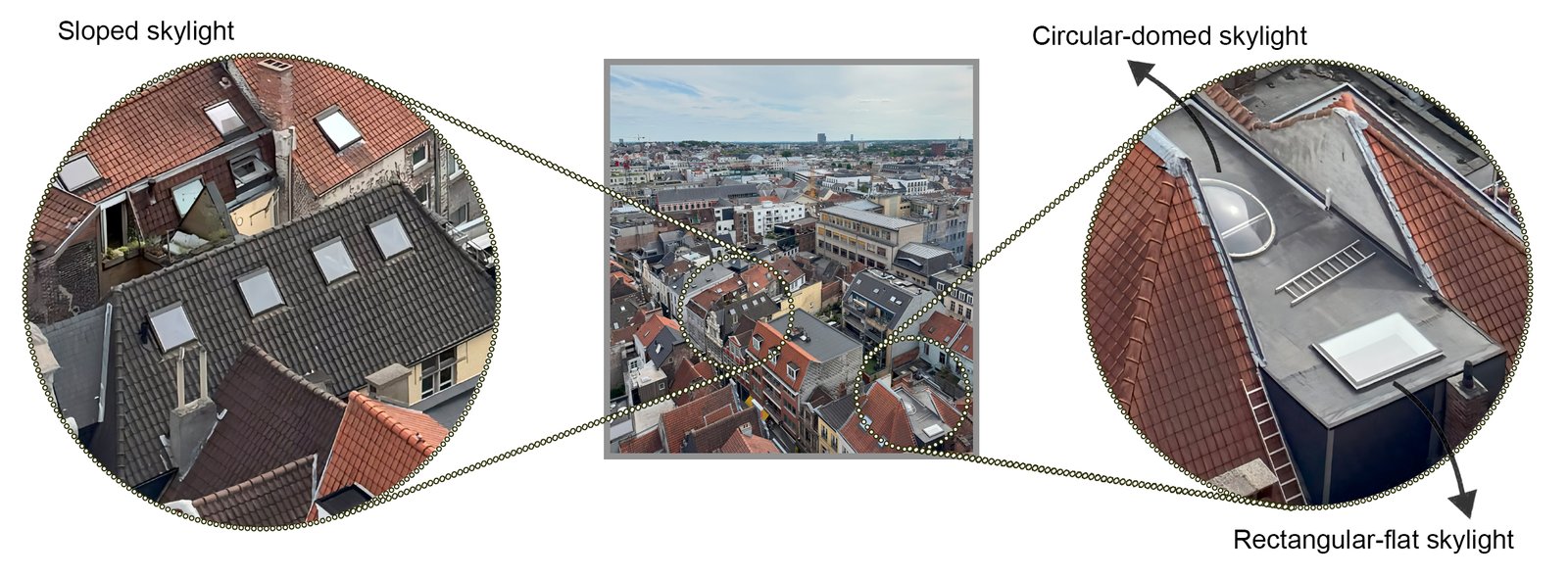

Historic buildings often rely on traditional structural systems -masonry construction, load-bearing walls, and timber post-and-beam frameworks [33,89] that demand extreme caution when integrating daylighting strategies. For instance, existing buildings often cost more and require complex engineering; checking floor and ceiling integrity is essential before adding skylights [46]. The installation of the new skylight may also require the replacement of the existing floors [49]. Beyond structural concerns, spatial characteristics also shape daylight potential: industrial buildings with generous ceiling heights and shallow depths are well-suited to daylight use, whereas those with narrow façades, deep plans, and thick walls require targeted interventions to reach interior zones [26,39,54]. At the urban scale, constraints -narrow streets, dense adjacency, and privacy concerns- often result in low window-to-wall ratios on ground floors, restricting daylight penetration and external views [33,90]. At the intervention level, measures such as enlarging openings, adding skylights, or replacing single glazing with multi-pane units can enhance thermal and daylight performance, they may risk compromising the structural integrity of masonry or timber elements [52], especially where aged materials are fragile and structural documentation is lacking. Even ostensibly non-structural measures, like light tubes or light shelves, may induce unforeseen stress. Upgrading glazing systems also demand careful attention to frame thickness, detailing, and compatibility, requiring collaboration with skilled craftsmen to preserve visual and material integrity [60]. Consequently, any daylighting enhancement must align with conservation principles addressed in policy documents of ICOMOS and UNESCO (reversibility, structural and heritage compatibility) [77,91].

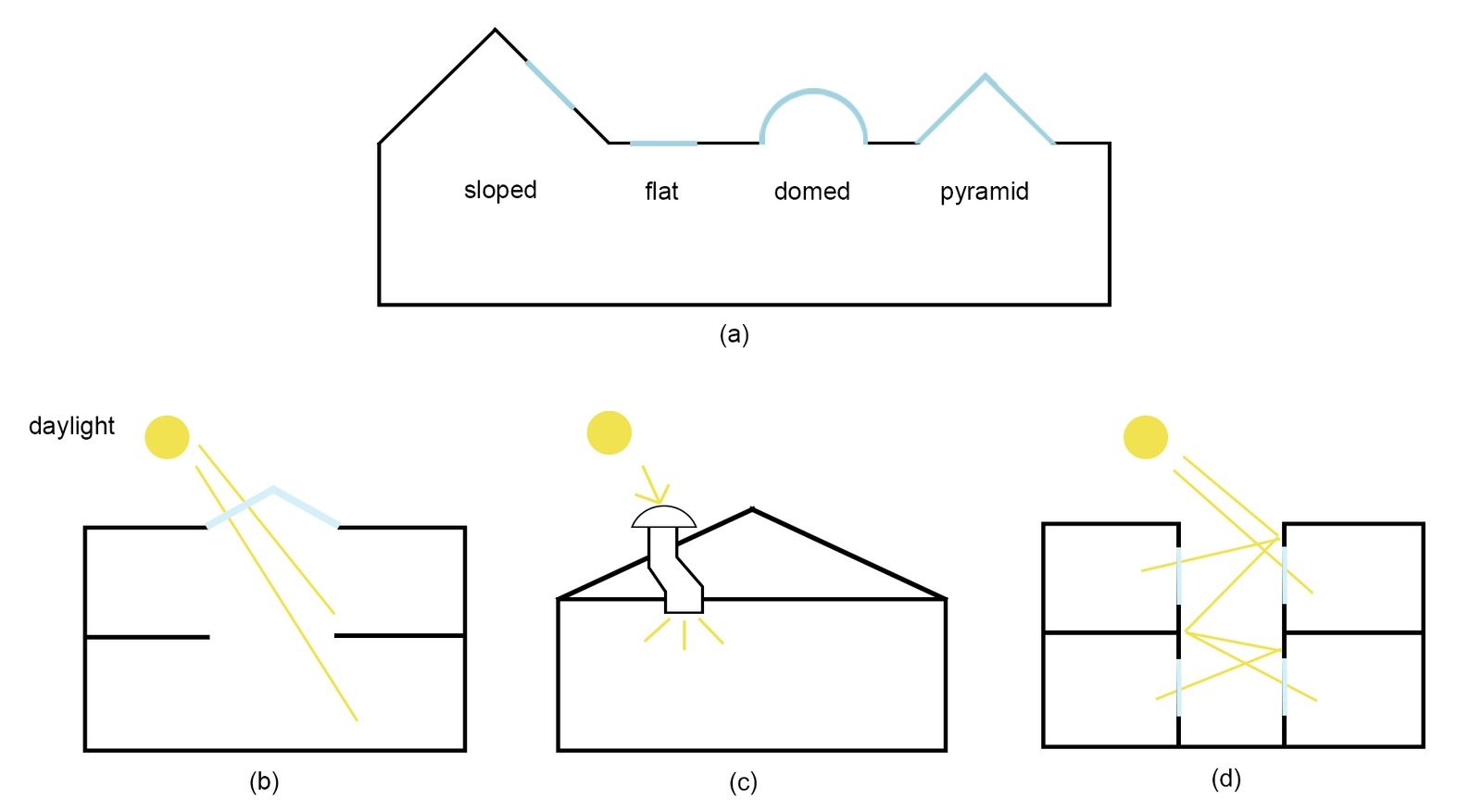

While window-based solutions play a significant role in enhancing visual and thermal comfort in historic buildings, they may not always be feasible due to façade intervention restrictions or structural limitations. In such cases, alternative strategies that improve daylight performance while preserving the building’s original façade appearance become relevant. One such strategy is to introduce daylight through the roof surfaces rather than directly altering façade elements. Roof-based daylighting systems offer unique opportunities to enhance interior illumination in historic buildings without altering their façades. Common solutions include skylights -sloped, flat, domed or pyramid-shaped- as well as atria, light tubes, and light wells (Fig. 4), each with distinct daylighting potential but also constraints imposed by conservation principles.

Evaluated interventions in the literature have ranged from installing new skylights [49] or modifying existing ones [10], to adding light tubes [41], integrating atrium [48] or employing transparent roof tiles [27]. However, roof-based systems may also impose additional structural loads, especially on historic timber beams or load-bearing roof trusses. To mitigate these risks, reinforcement strategies such as glass beam construction [92], lightweight stainless-steel framing [89], or carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) strengthening [93] can preserve structural integrity while enabling daylight integration.

3.3. Climate-Responsive Requirements

The typology of historic buildings is a direct product of the climatic conditions in which they were conceived, reflecting centuries of adaptation, resilience, and environmental knowledge. Several studies from diverse climates (Italy, Czech Republic, Egypt) confirmed that improvements in daylight performance have been provided by modifying the Visible Transmittance (VT) by changing the glazing type [10,47]. Higher visible transmittance (VT) glazing improves daylight penetration but may increase glare and reduce thermal insulation [57,60], thus necessitating integrated glare control solutions such as shading elements.

Shading elements - such as louvers, roller blind, fins, overhang, and curtain (Fig. 5) - integrated in the building design are commonly seen for protection from excessive daylight, block glare and mitigate overheating in countries with high annual daylight duration (Fig. 6). In contrast, in regions with low annual daylight, roof openings or skylights are often integrated (Fig. 7) to capture daylight. In some cases, such skylights were not part of the initial design but were introduced during later renovation interventions, responding to evolving needs for daylight.

Figure 6

Fig. 6. Exterior historic shading elements with various forms and materials (Authors’ archive).

Across the hot regions, the thick stone or adobe walls of historic buildings acted as formidable thermal barriers, insulating interiors from excessive heat while providing shade [94]. Courtyards, a defining feature of many historic buildings in hot climates, provided both cooler air and shaded areas [95]. When skillfully proportioned, these courtyards significantly enhanced environmental performance, optimizing daylight availability, improving occupant visual and thermal comfort, and reducing the demand for artificial lighting, which in turn yielded significant energy savings [96]. In cold climates, on the other hand, having thick external walls and insulated glazing are crucial strategies to prevent heat loss [97], while carefully placed and sized window openings ensure that interiors remain well daylit, even though long winter periods. Conversely, in hot regions where excessive daylight threatened both visual and thermal comfort, windows are deliberately kept small to avoid heat gain and glare [98]. These examples highlight the importance of climate-responsive design strategies that balance daylight availability with thermal comfort when planning interventions..

While these traditional climate-responsive features have proven effective for centuries, contemporary approaches increasingly incorporate advanced daylighting technologies -such as reflective systems- to further optimize daylight distribution and visual comfort under varying climatic conditions. Reflective daylighting systems can be categorized into two groups: ceiling-mounted solutions (ceiling reflectors and false ceilings), and light shelves which are positioned above upper windows’ interior, exterior or both sides [26,52]. Though they aim to maximize daylight receive to deeper areas and providing uniformity, there are some conflicting results in various climates, highlighting the importance of evaluating such interventions within the specific climatic context in which they are applied. For instance, incorporating light shelves resulted in improved daylighting in the city of Mersin, Turkey, characterized by the Mediterranean climate [73], whereas in Portland, Oregon, USA, with its temperate oceanic climate they behaved as a shading element and reduced daylighting levels in temperate climate [62]. Even in a study conducted in Erzincan, Turkey, which has a continental climate, light shelves were purposefully implemented in a continental climate, successfully mitigating direct and excessive daylight exposure, reducing overheating, and addressing the adverse impacts of climate change [23].

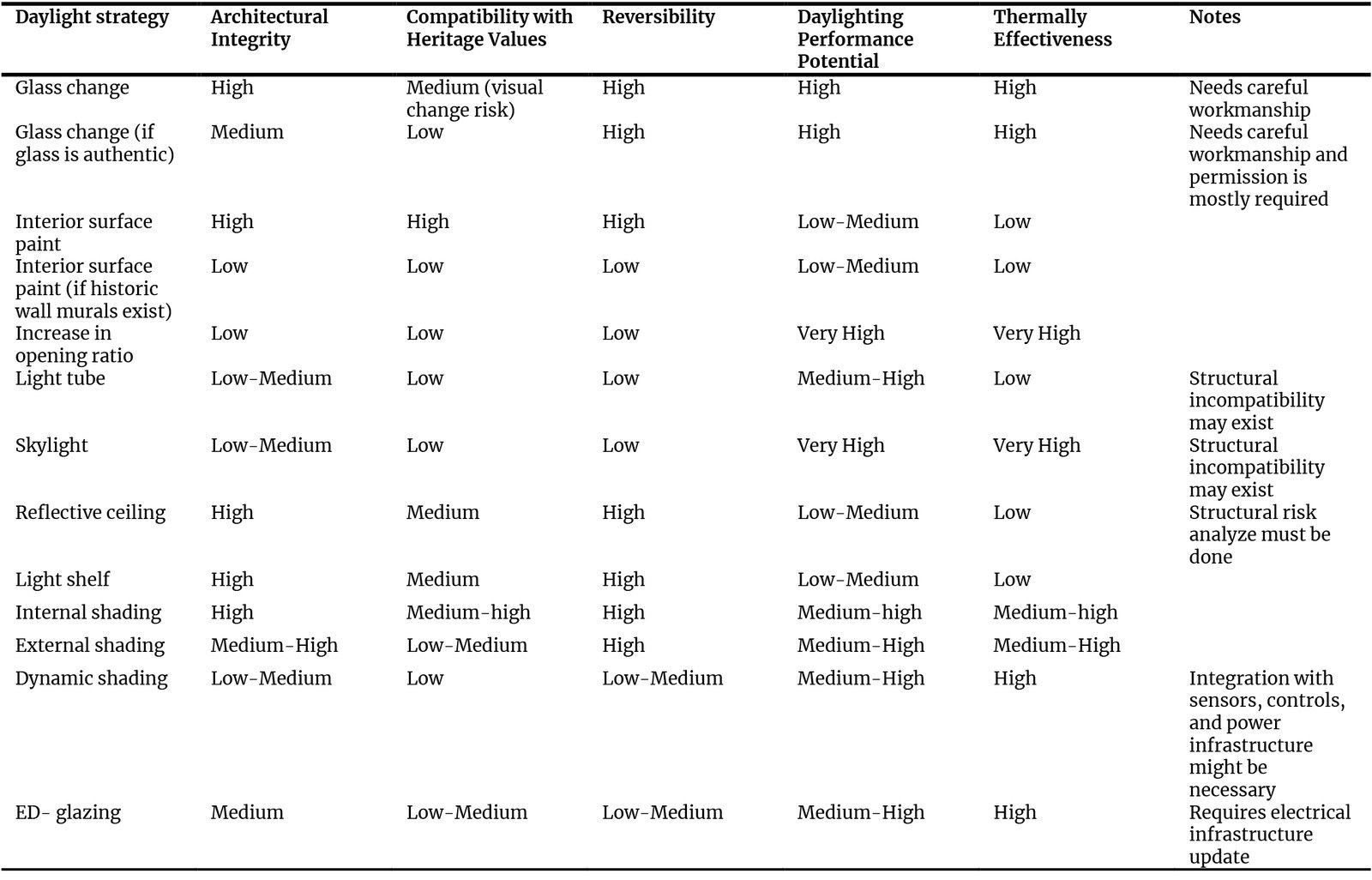

4. Discussion

This review reveals that while numerous daylighting interventions have been explored for historic buildings, their applicability is largely shaped by their heritage status, requirements, and limitations such as architectural integrity, compatibility with heritage value, and reversibility; building materials and structural concerns; and climatic conditions. Evaluations of proposed daylighting strategies within these themes are presented in Table 5.

The evaluation criteria in Table 4 were assigned by considering the degree of physical disturbance, visual impact, and material change involved in each strategy, as well as its reversibility and compatibility with heritage values. Architectural integrity reflects how minimally an intervention affects the historic fabric; compatibility indicates whether the strategy preserves authenticity and building character; and reversibility assesses the ease of removing the intervention without damage. In addition, daylighting performance potential and thermal effectiveness were evaluated based on findings reported in the reviewed studies regarding daylighting improvement, daylight distribution, solar control, and heat gain or loss. Accordingly, low-impact and easily reversible measures (e.g., light shelves, reflective ceilings) received higher integrity and compatibility scores, while strategies requiring mechanical components, structural changes, or electrical integration (e.g., dynamic shading, light tubes, skylights) were assigned lower values.

From a heritage conservation perspective, the literature consistently emphasizes that regulatory and conservation frameworks strongly restrict interventions in historic buildings. Especially in European contexts, legal provisions often prohibit modifying window sizes and adjusting façade components.

These strict regulations reflect a prevailing conservation philosophy of minimum intervention, which prioritizes safeguarding authenticity and heritage value over performance upgrades. Consequently, compliance with contemporary daylighting standards (EN 17037, IESNA, CIBSE, LEED, etc.) is often partial or entirely unattainable, generating a recurring tension between heritage preservation and contemporary building performance requirements. Despite the central role of these regulatory constraints, the extent to which the reviewed studies clearly address them varies considerably.

Strategies such as changing glazing systems, altering window-to-wall ratios, integrating skylights, or modifying wall compositions may be feasible during major renovations but are rarely acceptable in partially or fully protected buildings due to concerns about authenticity, integrity, and reversibility. Similarly, while dynamic shading and electrochromic glazing technologies can enhance daylighting, their permanence and impact on architectural character remain problematic within a conservation framework. This lack of explicit consideration of conservation status of the studied historic buildings raises questions about the practical applicability of many studies to real-world heritage contexts. Moreover, a limited number of studies (only about 7% of those reviewed) explicitly reference ICOMOS policy documents [22-25]. These policies highlight principles such as minimum intervention, reversibility, and respect for integrity, which directly shape both the extent and type of permissible alterations. The limited engagement with these principles suggests a need for stronger integration of conservation guidelines into research on historic building interventions.

From a material and structural perspective, the majority of cases highlight the use of traditional construction materials such as stone, brick, and timber-framed systems, occasionally complemented by vernacular solutions like mud block masonry, rubble stone, or thatch and wood structures. These reflect both regional construction cultures and long-standing building practices. Within the literature, the concept of preserving architectural integrity in relation to daylighting in historic buildings was most extensively discussed in 2024, with four studies addressing the issue, while further references appear in five studies published between 2001 and 2023. Many studies stress that interventions should be carefully designed to respect heritage values, ensuring that adaptations -such as shading devices, window modifications, or carefully designed roof interventions- enhance daylight performance without compromising the authenticity of the building envelope. This is particularly evident in the case of skylight integration, as it can improve daylighting without requiring major alterations to the façade. Prefabricated skylight systems designed for relatively quick installation were also among the methods proposed to improve daylighting; however, their application often entails high costs, engineering challenges, or even demolition of existing floors, which raises concerns regarding structural integrity.

From a climate-context perspective, environmental conditions are a decisive factor shaping conservation and daylighting strategies. In hot and arid or humid tropical climates, the focus is placed on solar control, dynamic shading, and the mitigation of ultraviolet radiation, which can severely damage interior artifacts through fading, discoloration, or structural deterioration. In continental and cold climates, conversely, strategies prioritize maximizing daylight access while maintaining thermal comfort. However, the literature reveals a geographical imbalance as visible in the extracted dataset (Table 2), while hot and tropical regions are extensively studied, historic buildings in temperate and Nordic climates remain underrepresented, despite their distinct challenges of optimizing daylight and reducing reliance on artificial lighting. Across different climatic contexts, the most common strategies include altering surface reflectance, modifying the visible transmittance (VT) of glazing, and introducing shading devices. Yet, their effectiveness varies considerably. For example, the performance of light shelves appeared to differ across climatic regions; however, this variation may also be attributable to their material, depth, and placement, indicating that climate cannot be regarded as the sole determinant.

5. Conclusion and future studies

This review highlights the importance of bringing together design strategies to increase daylight in historic buildings to jointly address the need to improve energy efficiency and protect cultural heritage. The research examined 54 studies, published between 2000 and 2025 that focused on daylighting improvement strategies in historic buildings, considering building functions, climate types, buildings’ heritage status, applicability, compatibility, and reversibility on design strategies. The findings obtained provide a basic framework to architects and researchers for the implementation of context-sensitive solutions by balancing conservation principles and technical interventions. These integrated approaches ensure that historic buildings both maintain their functionality in accordance with today’s conditions and are transferred to future generations. The findings also indicate that, in some cases, the building typology itself becomes a decisive factor. For example, studies focusing on certain building types (e.g., museums) often adopt historical perspective, however, their main emphasis lies in the preservation of artifacts or interior contents, while conservation measures concerning the buildings themselves -such as material integrity and structural preservation- are not the main focus in studies.

Findings highlight that effective daylighting in heritage contexts requires a multi-criteria approach that compromises energy efficiency goals with the preservation of architectural authenticity and integrity. Extending research to cover a broader range of climatic and geographical contexts is essential, as daylight optimization strategies must be adapted to local climatic conditions and the increasing variability imposed by climate change. A clear trend within the reviewed studies is the dominance of daylight-enhancing strategies, particularly roof-based systems and window-related adjustments. These interventions are often simpler to apply, less disruptive to building operations, and more affordable than alternatives such as advanced shading technologies or structural modifications, which may explain their high representation. Conversely, more specialized or costly strategies, including those addressing historic building features, remain relatively rare in the literature. This pattern suggests that research attention often aligns with practical feasibility and economic accessibility. Furthermore, precise classification of heritage protection levels is critical for aligning interventions with regulatory constraints. Future studies should examine the extent to which the proposed interventions coincide with accepted daylight standards and evaluate the updating of these standards in accordance with dynamic metrics. The creation of specially adapted daylighting guidelines for historic buildings can contribute to both achieving conservation goals and encouraging efficient daylight use.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK) through the 2211-A National PhD Scholarship Programs (Grant No.1649B032201072) and 2214-A International Research Fellowship Programme for PhD Students (Grant No.1059B142301161), which were granted to the main author.

Author Contributions

N.Sönmez: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, visualization, writing, editing of the original manuscript, and funding acquisition. A. CILASUN KUNDURACI: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and the writing, reviewing, and editing of the original manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Green Building Council, Bringing Embodied Carbon Upfront, Accessed: June 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://worldgbc.org/climate-action/embodied-carbon/ https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003527404-12

- R. Redden, R. H. Crawford, Valuing the environmental performance of historic buildings, Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, 28:1 (2021) 59-71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2020.1772133

- United Nations Environment Programme and Yale Center for Ecosystems + Architecture, Building Materials and the Climate: Constructing a New Future, (2023).

- K. M. Al-Obaidi, M. A. Ismail, A. M. Abdul Rahman, Assessing the Allowable Daylight Illuminance from Skylights in Single-storey Buildings in Malaysia: A review, International Journal of Sustainable Building Technology and Urban Development, 6:4 (2015) 236-248. https://doi.org/10.1080/2093761X.2015.1129369

- A. Ivanova, Thermal and Visual Performance of Vernacular Revival Buildings in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, Vienna University of Technology, (2021).

- P. M. Bluyssen, The Need for Understanding the Indoor Environmental Factors and Its Effects on Occupants through An Integrated Analysis, in: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/609/2/022001

- X.R. Bonnefoy, I.Annesi-Maesano, L. M. Aznar, M. Braubach, B. Croxford, M. Davidson, V. Ezratty, J. Fredouille, M. Gonzalez Gross, I. van Kamp, C. Maschke, M. Mesbah, B. Moissonnier, K. Monolbaev, R. Moore, S. Nicol, H. Niemann, C. Nygren, D. Ormandy, N. Röbbel, P. Rudnai, Review of Evidence on Housing and Health, in: Fourth Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health, Hungary, (2004).

- P. Höppe, Different Aspects of Assessing Indoor and Outdoor Thermal Comfort, Energy and Buildings, 34:6 (2002) 661-665. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7788(02)00017-8

- B. Antunović, M. Malinović, J. Rašović, S. Petrović, Daylight Performance in an Austrohungarian Heritage Building, AGG+, 1:8 (2020). https://doi.org/10.7251/aggplus2008008a

- Z. Shirzadnia, A. Goharian, M. Mahdavinejad, Designerly Approach to Skylight Configuration Based on Daylight Performance; Toward a Novel Optimization Process, Energy and Buildings, 286 (2023) 112970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.112970

- E. R. Sobhani, Role of Façade Elements in Daylight Control for Improving the Quality of Indoor Environment, Eastern Mediterranean University, (2019).

- M. Marzouk, M. ElSharkawy, A. Eissa, Optimizing Thermal and Visual Efficiency Using Parametric Configuration 0f Skylights in Heritage Buildings, Journal of Building Engineering, 31 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101385

- ICOMOS, The Venice Charter - International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites, (1964). Accessed: Nov. 25, 2024.

- D. A. Elsorady, Assessment of The Compatibility of New Uses for Heritage Buildings: The Example of Alexandria National Museum, Alexandria, Egypt, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 15:5 (2014) 511-521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2013.10.011

- M. Petzet, Principles of Preservation. An Introduction to the International Charters for Conservation and Restoration 40 Years after the Venice Charter, Munich: ICOMOS (2004) 7-29.

- UNESCO, Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, Including a Glossary of Definitions - Legal Affairs. Accessed: Aug. 11, 2025.

- N. R. Haddaway, M. J. Page, C. C. Pritchard, L. A. McGuinness, PRISMA2020: An R Package and Shiny App for Producing PRISMA 2020-Compliant Flow Diagrams, with Interactivity for Optimised Digital Transparency and Open Synthesis, Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18:2 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1230

- A. Cılasun Kunduracı, S. Karagözler, Z. Sevinç Karcı, Indoor Environmental Quality in Residential Care Facilities: A Scoping Review with Design Focus, Journal of Architectural Sciences and Applications, 8:1 (2023) 123-145. https://doi.org/10.30785/mbud.1223526

- M. Oner, K. Lenker, D. Durmus, Effects of Evening Indoor Light Exposure on Sleep and Circadian Functioning in Autistic People: A Scoping Review, Building and Environment, 280 (2025) 113138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2025.113138

- P. Lewis, R. Christoforou, P. P. Ha, U. Wild, M. Schweiker, T. C. Erren, Architecture, Light, and Circadian Biology: A Scoping Review, Science of the Total Environment, vol. 955 (2024) 177212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.177212

- Z. Munn, M. D. J. Peters, C. Stern, C. Tufanaru, A. McArthur, E. Aromataris, Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance For Authors When Choosing Between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach, BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18:143 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- R. Amoêda, S. Carneiro, Daylighting Simulation on Restoration Projects of Vernacular Architecture: An Application of Dialux ® Evo 9.1, in: HERITAGE 2020 - Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Heritage and Sustainable Development, 1 (2020) pp. 163-176.

- A. M. Top, A. Soyluk, İ. Ayçam, Analytical Study on Reducing the Heating Effects of Daylight and Improving Natural Lighting Performance at Erzincan Train Station in the Context of Climate Change, Journal of Daylighting, 11:2 (2024) 268-278. https://doi.org/10.15627/jd.2024.19

- V. Strazzeri R. Tiwari, Integrating Indigenous Lifestyle in Net-Zero Energy Buildings. A Case Study of Energy Retrofitting of a Heritage Building in the Southwest of Western Australia, Z. Allam, Ed., in Urban Sustainability, Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023, pp. 407-433. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-2695-4

- R. Prihatmanti, M. Y. Susan, Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Building and The Impact to The Visual Comfort: Assessed by The Lighting Quality, IPTEK Journal of Proceedings Series, (2017). https://doi.org/10.12962/j23546026.y2017i3.2443

- B. Alatawneh, H. Dofish, A. Dofish, Daylight Refinement of a Traditional Building in Hebron, Palestine, in: IARCSAS 1st International Architectural Sciences and Application Symposium, A. Gül, Ö. Demirel, and S. Seydosoğlu, Eds., Isparta, Turkey, 2021, pp. 1269-1279.

- J. Wu, Z. Li, T. Yang, L. Xie, J. Liu, Daylighting Enhancement in Traditional Military Settlement Dwellings of Xiangxi, China: A Study on Cost-Effective and Heritage-Consistent Renovation Approaches, Energy and Buildings, 316 (2024) 114356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2024.114356

- Q. Chen, J. Weng, Applying Ecotect Software to Analyze Natural Lighting of Traditional Dwelling Architecture-Experiences from the Huwan Village, Fuzhou City, Jiangxi Province, China, International Journal of Simulation: Systems, Science and Technology, 17:1 (2016). https://doi.org/10.5013/IJSSST.a.17.01.28

- S. Zhao, J. Diao, S. Yao, J. Yuan, X. Liu, M. Li, Seasonal Optimization of Envelope and Shading Devices Oriented Towards Low-Carbon Emission for Premodern Historic Residential Buildings of China, Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 64 (2024) 105452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2024.105452

- R. Gao, J. Liu, Z. Shi, G. Zhang, W. Yang, Patio Design Optimization for Huizhou Traditional Dwellings Aimed at Daylighting Performance Improvements, Buildings, 13:3 (2023) 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13030583

- Z. Zhou, C. Zhu, Z. Duan, Research on the Transformation Strategies of the Natural Lighting in the Traditional Silt Houses in Yunnan Province, in: International Conference on Architectural, Civil and Hydraulics Engineering (ICACHE 2015), Guangzhou, China, (2015). https://doi.org/10.2991/icache-15.2015.68

- D. Bustán-Gaona, Y. Jiménez-Sanchez, M. Del Pozo, S. Armijos, Metrics of Natural Light in Traditional Rural Housing in Ambato, in: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Institute of Physics, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1141/1/012007

- D. Bustán-Gaona, M. Ayala-Chauvin, J. Buele, P. Jara-Garzón, G. Riba-Sanmartí, Natural Lighting Performance of Vernacular Architecture, Case Study Oldtown Pasa, Ecuador, Energy Conversion and Management: X, 20 (2023) 100494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecmx.2023.100494

- V. R. M. Lo Verso, E. Fregonara, F. Caffaro, C. Morisano, G. Maria Peiretti, Daylighting as The Driving Force of The Design Process: From the Results of a Survey to The Implementation into an Advanced Daylighting Project, Journal of Daylighting, 1:1 (2014) 36-55. https://doi.org/10.15627/jd.2014.5

- C. Balocco, M. Cecchi, G. Volante, Natural Lighting for Sustainability of Cultural Heritage Refurbishment, Sustainability (Switzerland), 11:18 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184842

- F. Leccese, G. Salvadori, G. Tambellini, Z. T. Kazanasmaz, Application of Climate-Based Daylight Simulation to Assess Lighting Conditions of Space and Artworks in Historical Buildings: The Case Study of Cetacean Gallery of the Monumental Charterhouse of Calci, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 46 (2020) 193-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2020.06.010

- C. Balocco, E. Frangioni, Natural lighting in the Hall of Two Hundred. A Proposal for Exhibition of Its Ancient Tapestries, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 11:1 (2010), 113-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2009.02.005

- A. S. M. Shahbudin, N. Ainsyah Zulkifli, J. Muhamad, A. S. A. M. Khair Sayed, H. Salam, Daylighting Analysis: External Shading Device Effect Illuminance Reading of Assembly Hall Sultan Abdul Hamid College, International Journal of Business and Technology Management, 6: S1 (2024) 163-177.

- M. Stojkovic, M. Pucar, A. Krstic-Furundzic, Daylight Performance of Adapted Industrial Buildings, Facta Universitatis - Series: Architecture and Civil Engineering, 14:1 (2016) 59-74. https://doi.org/10.2298/FUACE1601059S

- A. Michael, C. Heracleous, A. Savvides, M. Philokyprou, Lighting Performance in Rural Vernacular Architecture in Cyprus: Field Studies and Simulation Analysis, in: PLEA 2015, 2015.

- N. Sönmez, A. C. Kunduracı, C. Çubukçuoğlu, Daylight Enhancement Strategies Through Roof for Heritage Buildings," Journal of Daylighting, 11:2 (2024) 234-246. https://doi.org/10.15627/jd.2024.17

- M. Rajapaksha, M. Kariyawasam, Enhancing Thermal and Daylight Performance of Historic Buildings with Passive Modifications; A Tropical Case Study, KDU Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 6:1 (2024) 134-144. https://doi.org/10.4038/kjms.v6i1.117

- zzzzzzzzzO. K. Overen, E. L. Meyer, G. Makaka, Daylighting Assessment of a Heritage Place of Instruction and Office Building in Alice, South Africa, Buildings, 13:8 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13081932

- N. Sönmez, A. Cılasun Kunduracı, Enhancing Daylight Availability in Historical Buildings through Tubular Daylight Guidance Systems: A Simulation-Based Study, Light & Engineering, 31:6 (2023) 121-126. https://doi.org/10.33383/2023-053

- S. Szentesi-Nejur, A. Nejur, F. De Luca, P. Madelat, Early Design Clustering Method Considering Equitable Daylight Distribution in The Adaptive Re-Use of Heritage Buildings, in: eCAADe 2023: Digital Design Reconsidered, 2023, pp. 105-114. https://doi.org/10.52842/conf.ecaade.2023.2.105

- R. Wood, An Analysis of Skylight and Alternative Applications in the Adaptive an Analysis of Skylight and Alternative Applications in the Adaptive Reuse of The Ridgedale Mill Reuse of The Ridgedale Mill, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, 2023.

- M. Marzouk, M. ElSharkawy, A. Mahmoud, Optimizing Daylight Utilization of Flat Skylights n Heritage Buildings, Journal of Advanced Research, 37 (2022) 133-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2021.06.005

- F. Piraei, B. Matusiak, V. R. M. Lo Verso, Evaluation and Optimization of Daylighting in Heritage Buildings: A Case-Study at High Latitudes, Buildings, 12:12 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12122045

- A. Lo Faro F. Nocera, Daylighting Design for Refurbishment of Built Heritage: A Case Study, in: Sustainability in Energy and Buildings 2021, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6269-0_29

- S. M. Mirkazemi, Y. Mousavi, The Way of Using Daylight in the Process of Historic Buildings Reconstruction Via New Construction Technology (Case study: Safa Bath)," Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education, 12:13 (2021) 4459-4464.

- M. Scorpio, G. Ciampi, N. Gentile, S. Sibilio, Low-Cost Smart Solutions for Daylight and Electric Lighting Integration in Historical Buildings, in: Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Institute of Physics, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2069/1/012157

- K. Soleimani, N. Abdollahzadeh, Z. S. Zomorodian, Improving Daylight Availability in Heritage Buildings: A Case Study of Below-Grade Classrooms in Tehran, Journal of Daylighting, 8:1 (2021) 120-133. https://doi.org/10.15627/jd.2021.9

- A. Ghosn, S. M. C. Furuyama, J. P. L. Trigo, C. Candido, A. Prata-Shimomura, A. Ghosn, Daylight Performance Evaluation in a Modern Brazilian Heritage Building Analysing Daylight Assessment Tools, in: PLEA 2020 A CORUÑA Planning Post Carbon Cities, 2020.

- W. Iyati, A. P. Riski, J. Thojib, Strategies to Improve Natural Lighting in Deep-Plan Cultural Heritage Buildings in the Tropics," in: Proceedings of the International Conference of Heritage & Culture in Integrated Rural-Urban Context (HUNIAN 2019), 2020. https://doi.org/10.2991/aer.k.200729.014

- A. H. Mahmoud, M. M. Elsharkawy, M. M. Marzouk, Experimental Investigation of Daylight Performance in an Adapted Egyptian Heritage Building, Journal of Engineering and Applied Science, 67:6 (2020) 1193-1212.

- M. Marzouk, A. Eissa, M. ElSharkawy, Influence of Light Redirecting Control Element On Daylight Performance: A Case of Egyptian Heritage Palace Skylight, Journal of Building Engineering, 31 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101309

- J. Mohelníková, M. Novotny, P. Mocová, Evaluation of School Building Energy Performance and Classroom Indoor Environment, Energies, 13:10 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/en13102489

- M. Scorpio, G. Ciampi, A. Rosato, L. Maffei, M. Masullo, M. Almeida, S. Sibilio, Electric-Driven Windows for Historical Buildings Retrofit: Energy and Visual Sensitivity Analysis for Different Control Logics, Journal of Building Engineering, 31 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101398

- K. A. Al-Sallal, A. R. AbouElhamd, M. B. Dalmouk, UAE Heritage Buildings Converted into Museums: Evaluation of Daylighting Effectiveness and Potential Risks on Artifacts and Visual Comfort, Energy and Buildings, 176 (2018) 333-359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.06.067

- F. Nocera, A. L. Faro, V. Costanzo, C. Raciti, Daylight Performance of Classrooms in a Mediterranean School Heritage Building, Sustainability (Switzerland), 10:10 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103705

- I. Bournas, M. Abugabbara, A. Balcerzak, M. C. Dubois, S. Javed, Energy Renovation of an Office Building Using a Holistic Design Approach, Journal of Building Engineering, 7 (2016) 194-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2016.06.010

- L. Sanchez, N. Vipond, N. Papaefthimiou, M. Manzi, J. Brandt, S. Weber, J. Peel, Bora Architects, Daylight Analysis: Analayzing Daylight Autonomy in the Early Phases of Design on an Adaptive Reuse Project, Portland State University, 2016.

- L. Bellia, F. R. D'Ambrosio Alfano, J. Giordano, E. Ianniello, G. Riccio, Energy Requalification of a Historical Building: A Case Study, Energy and Buildings, 95 (2015) 184-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2014.10.060

- M. Ghasempourabadi, A. Arshadi, A. Ghaedi, S. Shahri, High-Performance Renovation of Iranian Historical Buildings to Substitute Active Lighting Systems with Natural Light (Case Study: Shahi Bank, Tehran), Energy Procedia, 78 (2015) 777-781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2015.11.093

- J. Mardaljevic, S. Cannon-Brookes, K. Lithgow, N. Blades, Illumination and Conservation: A Case Study Evaluation of Daylight Exposure for an Artwork Displayed in an Historic Building, in: CIE 28th Session, 2015.

- R. Ajmat, M. P. Zamora, J. Sandoval, Daylight in Museums: Exhibition vs. Preservation, Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture XII the Built Environment, 118 (2014) 195-206. https://doi.org/10.2495/STR110171

- N. Ahmad, S. S. Ahmad, A. Talib, Surface Reflectance for Illuminance Level Control in Daylit Historical Museum Gallery Under Tropical Sky Conditions, Advanced Materials Research, 610-613 (2013) 2854-2858. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.610-613.2854

- M. Andersen, S. J. Gochenour, S. W. Lockley, Modelling 'Non-Visual' Effects of Daylighting in a Residential Environment, Building and Environment, 70 (2013) 138-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2013.08.018

- C. S. Kim, S. J. Chung, Daylighting Simulation as an Architectural Design Process in Museums Installed with Toplights, Building and Environment, 46:1 (2011) 210-222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2010.07.015

- H. Elkadi, S. Al-Maiyah, Daylight for Sustainable Development of Historic Sites, in: ANZAScA 2009: Performative Ecologies in the Built Environment: Sustainability Research Across Disciplines, Launceston, 2009.

- C. Balocco, R. Calzolari, Natural Light Design for an Ancient Building: A Case Study, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 9:2 (2008) 172-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2007.07.007

- Y.-Y. E. Ng, L. Khee Poh, W. Wei, T. Nagakura, Advanced Lighting Simulation in Architectural Design in the Tropics, Automation in Construction, 10 (2001) 365-379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0926-5805(00)00053-4

- T. Kemer, N. M. Çelebi, Tarihi Yapıların Yeniden İşlevlendirilmesi ve Gün Işığından Maksimum Yararlanılması Hakkında Bir Öneri, in: Çukurova 13th International Scientific Researches Conference, Adana, 2020, pp. 188-198.

- ISC20C, ICOMOS, Madrid Document Approaches for the Conservation of Twentieth-Century Architectural Heritage, 2012.

- Australia ICOMOS, The Burra Charter: the Australia ICOMOS charter for places of cultural significance, 2013.

- ICOMOS, ICCROM, UNESCO, The NARA Document on Authenticity, 1994.

- ICOMOS, ICOMOS Charter - Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage. Accessed: Feb. 06, 2025.

- D. Dungworth, The Value of Historic Window Glass, The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 2:1 (2011) 21-48. https://doi.org/10.1179/175675011X12943261434567

- Historic England, Wall Paintings Anticipating and Responding to their Discovery, 2018.

- P. Roca, P. B. Lourenço, A. Gaetani, Historic Construction and Conservation Materials, Systems and Damage, Historic Construction and Conservation: Materials, Systems and Damage, Routledge: New York, 2019 pp. 1-324. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429052767

- D. Dungworth, Historic Window Glass: The Use of Chemical Analysis to Date Manufacture, Journal of Architectural Conservation, 18:1 (2012) 7-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556207.2012.10785101

- E. S. Abdulahaad, Z. H. Ra'ouf, V. A. A. B. M. Hasan, Reconsidering the Transparency of Contemporary Architecture and Sustainability Through Development of Glass Technology, International Journal of Design and Nature and Ecodynamics, 18:5 (2023)1111-1119. https://doi.org/10.18280/ijdne.180512

- Historic England, Energy Efficiency and Historic Buildings Secondary Glazing for Windows, 2012.

- D. Exner, J. Rose, É. Héberlé, S. Mauri, A. Rieser, Conservation compatible energy retrofit technologies: Part II: Documentation and assessment of conventional and innovative solutions for conservation and thermal enhancement of window systems in historic buildings, IEA Solar Heating and Cooling Programme, 2021. https://doi.org/10.18777/ieashc-task59-2021-0005

- N. Heath, P. Baker, Slim-Profile Double-Glazing in Listed Buildings: Re-Measuring the Thermal Performance, Historic Scotland, 2013.

- Gowercroft, What is Vacuum Glazing? Accessed: June 19, 2025.

- Stockfilms, Conserving an Historic Heritage. Accessed: June 19, 2025.

- N. H. Matin, A. Eydgahi, P. Matin, The Effect of Smart Colored Windows on Visual Performance of Buildings, Buildings, 12:6 (2022) 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12060861

- M. Corradi, A. I. Osofero, A. Borri, Repair and Reinforcement of Historic Timber Structures with Stainless Steel-A Review, Metals 2019, 9:1 (2019) 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/met9010106

- R. Şahin, A. E. Dinçer, Evaluating the Design Principles of Traditional Safranbolu Houses, Buildings 2024, 14:8 (2024) 2553. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14082553

- UNESCO, Recommendation Concerning the Protection, at National Level, of the Cultural and Natural Heritage, 1972.

- A. Jóźwik, Glass Beams Used in Steel-glass Roofs for the Adaptive Reuse of Historic Buildings, Civil and Environmental Engineering Reports, 34:3 (2024)136-153. https://doi.org/10.59440/ceer/190880

- A. Kheyroddin, M. H. Saghafi, S. Safakhah, Strengthening of Historical Masonry Buildings with Fiber Reinforced Polymers (FRP), Advanced Materials Research, 133-134 (2010) 903-910. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.133-134.903

- G. S. Austin, Adobe as a Building Material, New Mexico Geology, 6:4 (1984) 69-71. https://doi.org/10.58799/NMG-v6n4.69

- R. G. Carlos, M. D. M. Eduardo, G. M. Carmen, L. C. Victoria, Tempering Potential-Based Evaluation of the Courtyard Microclimate as a Combined Function of Aspect Ratio and Outdoor Temperature, Sustainable Cities and Society, 51 (2019) 101740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101740

- I. Acosta, C. Varela, J. F. Molina, J. Navarro, J. J. Sendra, Energy Efficiency and Lighting Design in Courtyards and Atriums: A Predictive Method for Daylight Factors, Applied Energy, 211 (2018) 1216-1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.11.104

- L. Yang, J. C. Lam, C. L. Tsang, Energy Performance of Building Envelopes in Different Climate Zones in China, Applied Energy, 85:9 (2008) 800-817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2007.11.002

- Ö. Atalan, Windows as Architectural Building Components and Examples of Their Applications of Traditional Buildings in Different Locations, Jass Studies-The Journal of Academic Social Science Studies, 15:93 (2022) 127-142. https://doi.org/10.29228/JASSS.66879

2383-8701/© 2026 The Author(s). Published by solarlits.com. This is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

HOME

HOME Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5 Figure 6

Figure 6 Figure 7

Figure 7 Table 1

Table 1 Table 2

Table 2 Table 3

Table 3 Table 4

Table 4 Table 5

Table 5